Cora Jeffers: A Visionary in Education and Beyond

Cora Doolittle Jeffers spent nearly sixty years shaping education in the Upper Peninsula. Her devotion to students and Adams Township schools helped transform the district into a place known across Michigan for strong teaching, steady expansion, and genuine opportunity. She opened doors for the students of Painesdale High School and beyond, championing physical education long before it was common and standing firm for women’s right to vote in the Copper Country. Her life is filled with remarkable achievements, and each one reflects a woman whose influence reached far beyond the classroom.

Charles Doolittle and his wife, Martha (Dole) Doolittle, lived humbly as farmers in rural Wheatland Township, Michigan, when their daughter Cora was born on April 1, 1871. Wheatland Township, about 60 miles north-east of Grand Rapids, is still a small area but when Cora was a child, it would have been incredibly rural, with no incorporated villages and only sparsely populated farms and rough dirt roads. The family would have been self-sustaining through the intense work of gardening, farming, canning, taking care of animals, etc. This hard work included the children, and they would have done jobs around the home and farm from the time they were small, which certainly gave Cora the foundation of discipline she showed later through her many accomplishments.

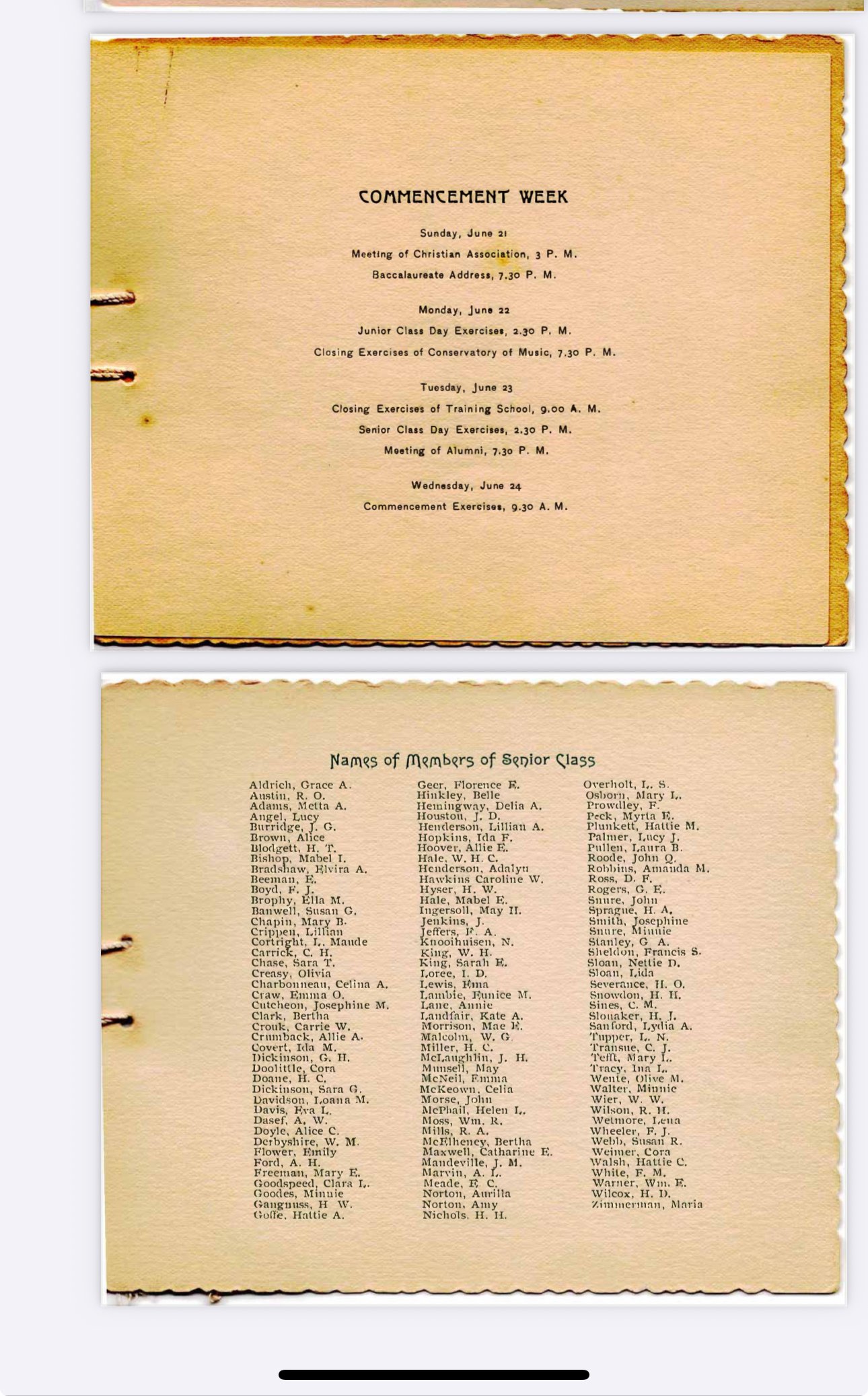

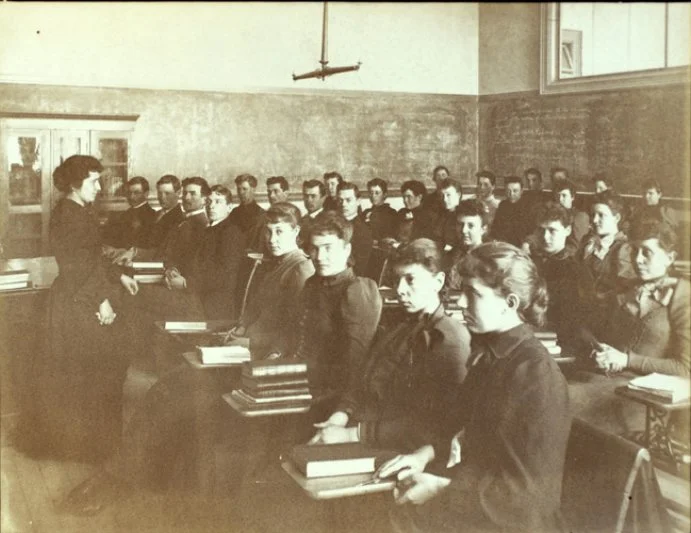

Cora, along with her siblings Martha, Inez, and Stewart, attended a small schoolhouse nearby, as many Michigan schoolchildren did at the end of the 19th century. As there was not yet any formal education structure or rules on compulsory education in Michigan, there was no high school available for Cora to attend from her isolated farm. She had to stop school sometime before completing a diploma, which must have devastated the curious and bright young woman. Showing her ambitions early and, because she could no longer be a student, she instead became a teacher in a local schoolhouse at only 16. There, in the schoolroom amongst students, Cora knew she had found her place. After taking an assortment of entrance exams in subjects such as Grammar and Geography due to her lack of diploma, Cora joined the Michigan State Normal School (which later became Eastern Michigan University) in the fall of 1887. It would have been a big adjustment from the farmhouse to the busy streets of Ypsilanti, but 16-year-old Cora was determined in her decision to become an educator.

Among her classmates at the teaching school (not yet designated as a “college”) was a young man from Napoleon, Michigan, Fred Jeffers. While both shared similar goals, their lives to that point had been very different. Fred had had a more difficult upbringing. He was born in Ohio but, along with a brother, was sent to a Boston orphanage after his parents died when he was a young child. He was later adopted by a couple in Michigan.

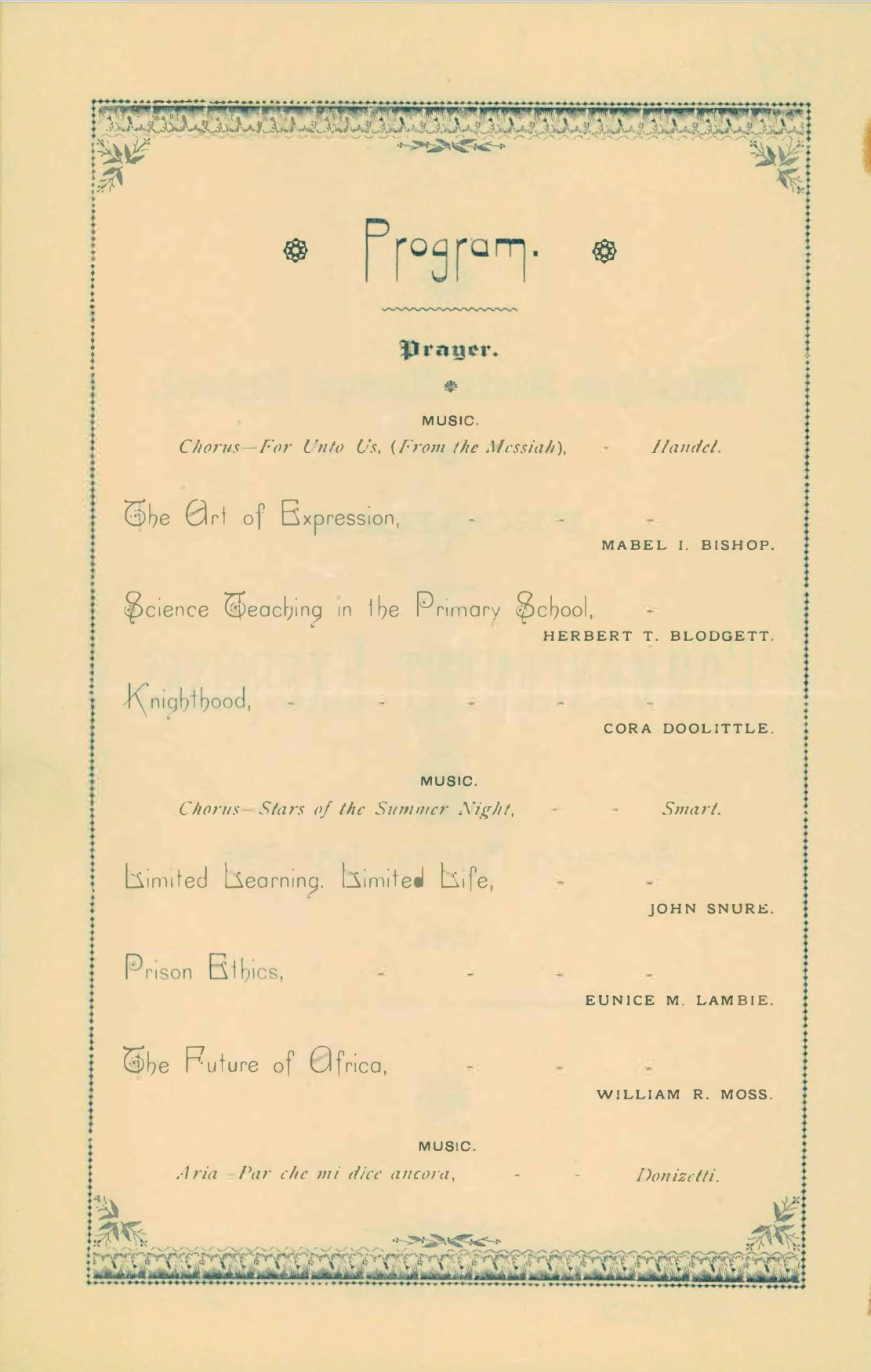

It is unknown when the relationship between Fred and Coras became romantic, but the earliest indication of pair knowing each other was that they both are listed as participants in the school debate club. In May of 1890, the school held its “Normal News Oration Contest,” and both Cora and Fred gave persuasive speeches. Cora’s “The Awkward Squad,” an allegory about American being a ship sailing through rough weather, was not selected as a winner but Fred’s “The Pen is Mightier Than the Sword,” self-explanatory, received second place in the men’s category.

Both graduating cum laude, Cora and Fred were each selected to speak at the 1891 Michigan State Normal School commencement ceremony. Cora’s address was titled “Knighthood” while Fred’s discussed “The Impatience of Modern Civilization.” Cora, a farm girl without a high school education, had completed an impressive four-year teaching degree before the age of 21. The Ypsilanti Commercial noted in their coverage of the event that “[the speakers] acquitted themselves so well that it was the almost unanimous opinion of the immense audience, that the Normal Commencement never went off so well before.”

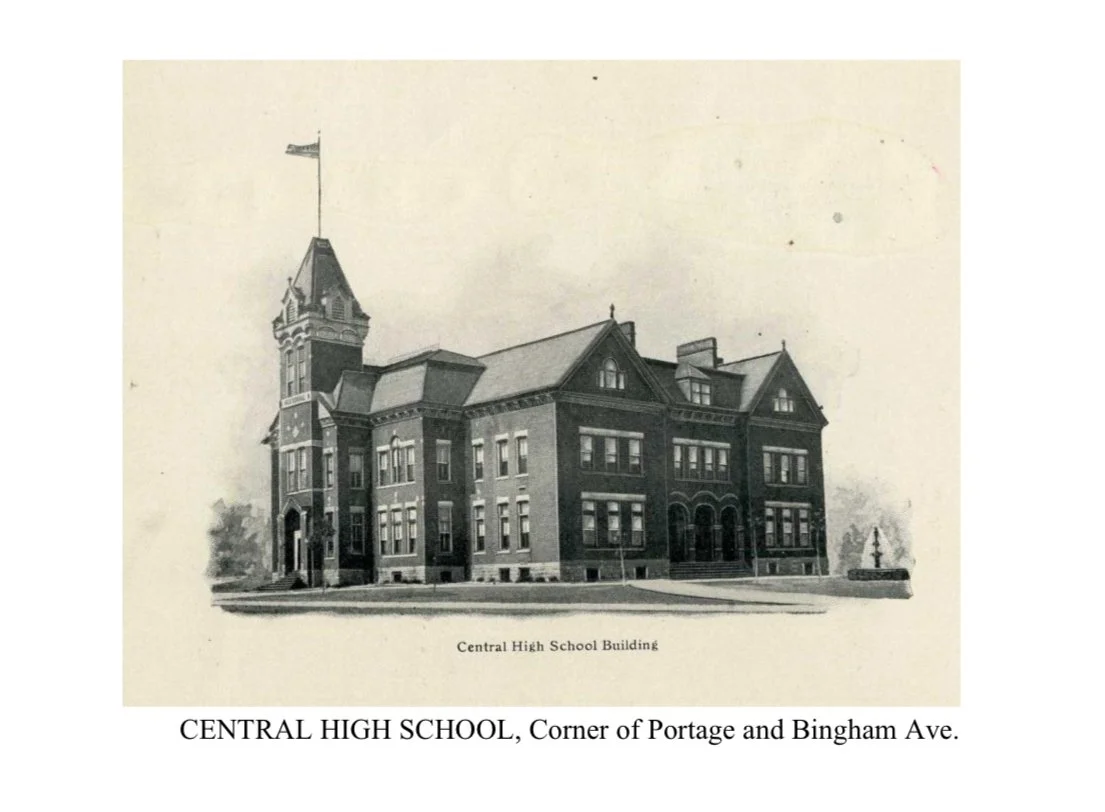

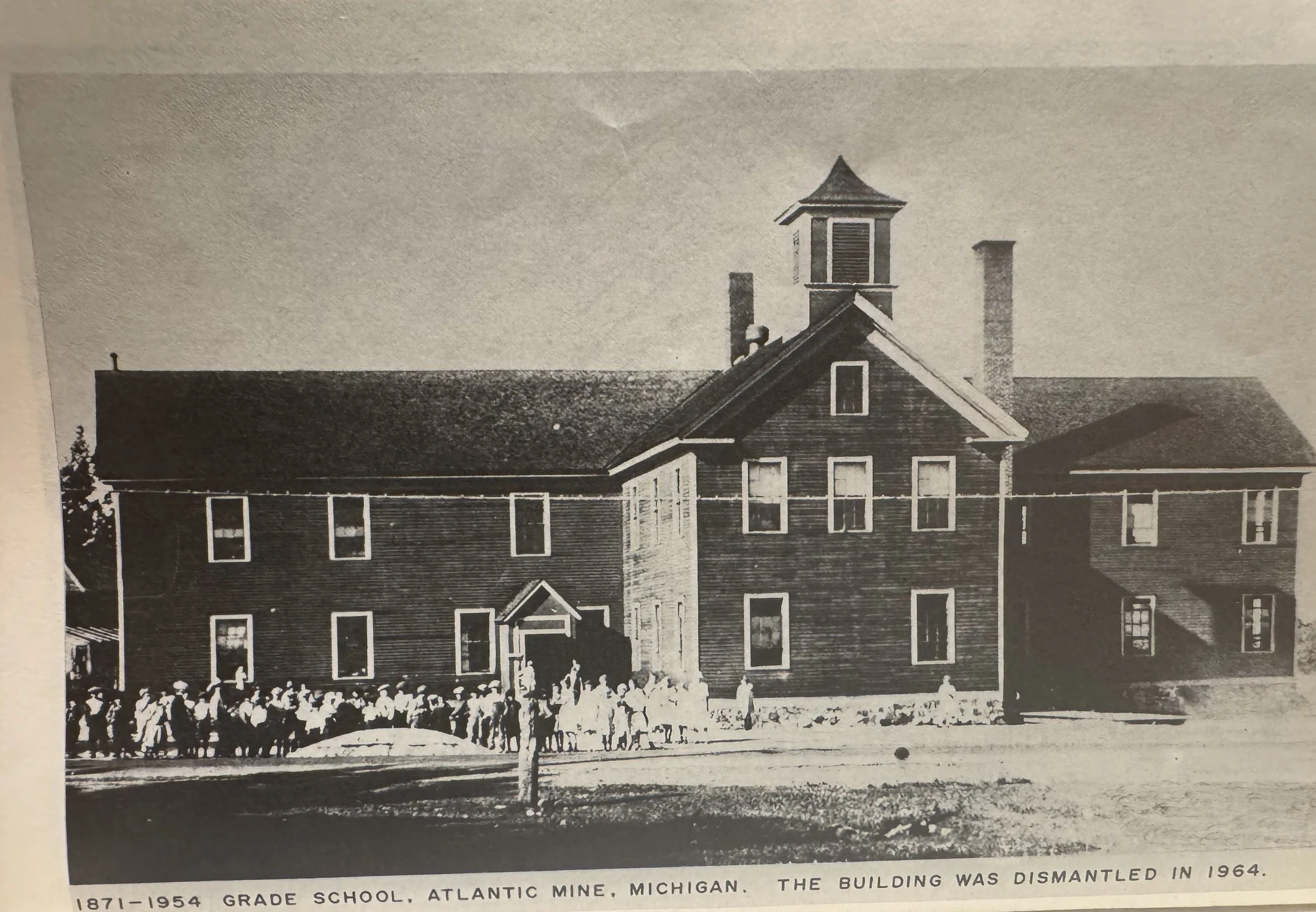

That fall, the pair boarded the steamship China in Detroit together. It was headed north but the couple had separate destinations. Cora would be teaching both reading and elocution at the Central High School in Sault Ste Marie, Michigan, while Fred would be continuing with the ship to the Copper Country. He was to be the new principal at the Atlantic Mine school, part of the Adams Township school district. While Cora was surely nervous about her first full-time teaching position, Fred had more reason to be unsure of his future. The Atlantic Mine school had gone through four principals in a year due to the rowdy nature of the male students. According to Rugani in his book Adams Township Schools, the boys would make it their goal to cause the principal to resign, whomever he was, “bruised battered and beaten.” The Secretary of the district, Mr. Edwards, wrote to the Michigan State Normal School specifically asking for a recommendation on someone who could handle the “tough-guy sons of immigrants” (Rugani). Fred, a man of large stature and a former baseball player and successful boxer, was up for the challenge.

Fred’s first day has become district and local lore. A male student was roughhousing and not listening to the new principal, disrespecting him in front of the other students. Fred’s reaction left the ringleader “sprawling on the classroom floor” (Rugani). The student’s angry father came to Fred upset but left as his friend. Allegedly, the student in question was an excellent student after the altercation and Mr. Jeffers was thereafter a respected member of the administration by both the students and the parents.

Cora’s tenure in Sault Ste Marie was short-lived but successful. She became principal during her second year there, from 1892-1893. This is an impressive accomplishment for a 22-year-old woman even now but was even more unusual at a time when women did not hold many positions of power in education. She retained her title when moving across the Upper Peninsula to Atlantic Mine, where she moved to join her new husband Fred in 1894. A position as superintendent had been created for the impressive new principal who had been able to get a handle of the rowdy boys of the school. The Board of Education was eager to hire his new bride, whom they were undoubtedly also impressed by. The couple would continue to teach together “shoulder-to-shoulder,” as many sources explain it, for the next 55 years.

Their new home, Atlantic Mine, was centered around the Atlantic Mining Company. The small wooden homes were filled with families of immigrants from places like Cornwall, Italy, and Finland. There were several saloons and general stores in town, but the streets were unpaved and social lives focused on church and community halls. The poor residents of the town did not value education and no high school was available for the students. The Atlantic Mine school stopped in eighth grade. However, the charismatic Fred and confident Cora soon charmed the local parents into allowing their children to complete their high school education. The first graduating class of the Atlantic Mine school was in 1897. The eight graduates were celebrated by their entire community. A gala event where the graduating students each gave persuasive speeches, no doubt coached by their administrators who were seasoned orators, was a tremendous success.

Cora and Fred quickly recognized that the township needed a more central secondary school that could serve the growing population of mining families scattered across Atlantic Mine, Painesdale, Baltic, Trimountain, and the surrounding locations. By the early 1900s the Copper Range Mining Company had expanded to Painesdale, a town a few miles west of Atlantic Mine. It was decided that the new central high school should be built in Painesdale. Painesdale High School, along with a home for the superintendent and principal across the street, was completed in 1909. The new railway depots available there and in the other township towns created the idea for a Copper Range railway school train. Students from places like Freda, Beacon Hill, Edgemere, Stanwood, Redridge, Salmon Trout, and Obenhoff, all needed to get to the high school in Painesdale for class in the morning and return home each evening. According to Copperrange.org, “This special school train was the first and only one in the nation and carried about three hundred children [daily].” It ran until 1942, when transportation was changed to bussing due to cost.

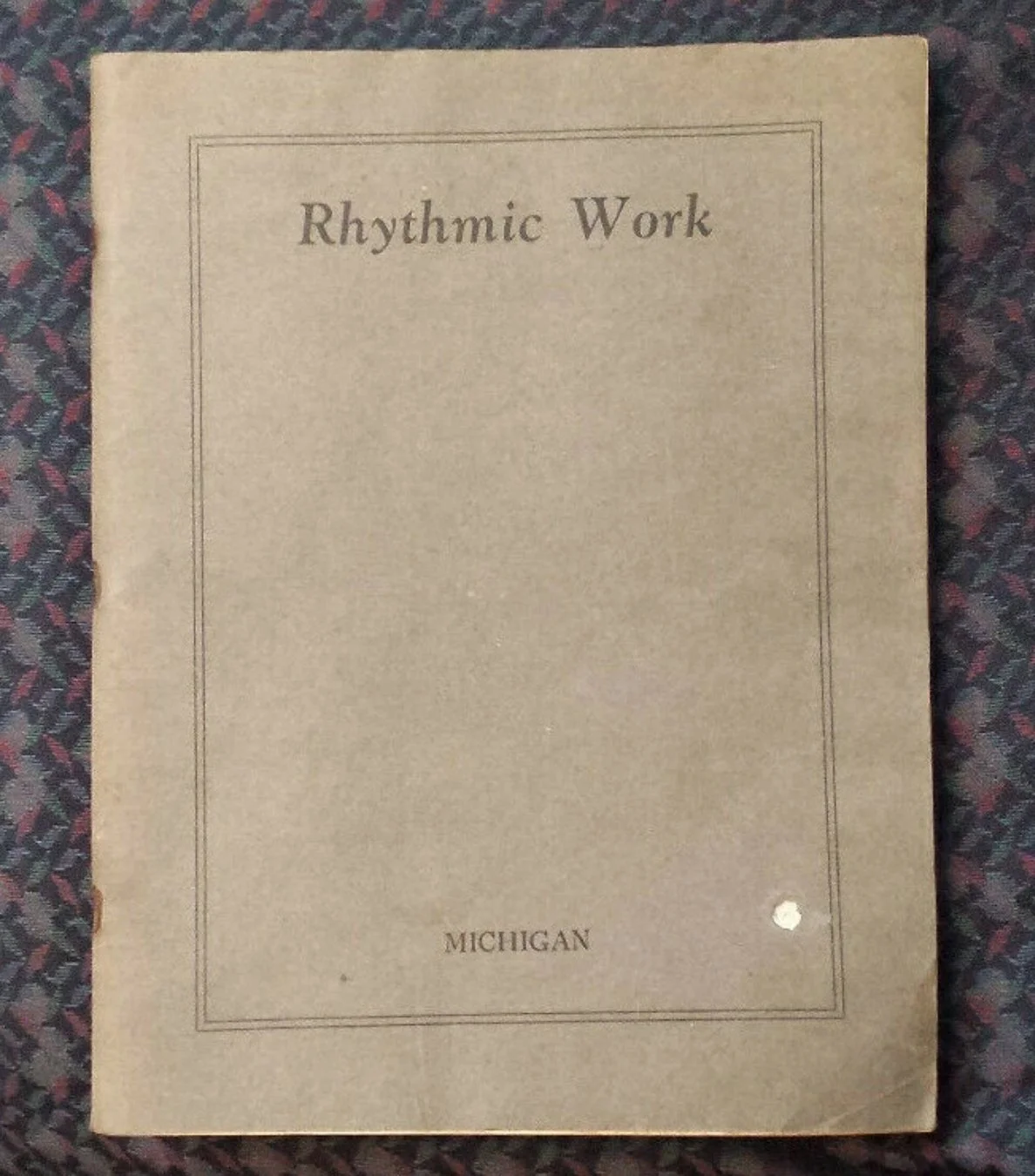

In 1909, Cora received an honorary Master of Pedagogy (the study of teaching) from Eastern Michigan University. Always aiming to further grow as both a person and as an educator, she then took a sabbatical to the east coast to learn more about physical education. Physical education, sometimes called “rhythmic movement” then, was a new subject area and Cora was extremely interested in bringing its benefits to the students of Adams Township. First, she studied dance and physical education instruction at the impressive Sargant School, which is now part of Boston University. After completing the program in Massachusetts, she continued on to New York and took rhythmic work classes with the ballet of the Metropolitan Opera Company. Upon her return to Painesdale, she soon had the students doing synchronized military drills and calisthenics. For the next four decades in her role as Principal, she would create and teach many physical education classes. In the 1920s she released a P.E. textbook, Rhythmic Work, which was acquired by the state of Michigan to distribute to schools across the state. The book was so successful that “physical education teachers from miles around… came to view and learn from carefully choreographed routines presented by… her students;” these routines included “gymnastics, dance, and precision marching” (Rugani).

It cannot be overstated how instrumental Cora, along with Fred, was in the suffragist movement in Houghton County and beyond in the Upper Peninsula. Not only was she Chairman of the Houghton County Equal Suffrage Committee, but she and Fred both used their impressive public speaking skills to create hope within as well as educate the citizens of the Copper Country on the women’s right to vote. In 1912 an article in The Calumet News explained that Cora had given a “masterly address” about women’s suffrage at a meeting of the Calumet Women’s Club. Cora told the crowd of women and “one male reporter” that women’s ability to vote was not an option, but a right. She was confident that, like the end of slavery, women gaining the right to vote was inevitable.

“Voting is a right, a privilege, and a duty. Men have it and women haven’t. We are demanding it,” she said to the gathering and added, “and we have a great many good men within our ranks who are also demanding it for us.” One main argument of those against women voting was that women should only be worried about their home and not politics. Cora did not agree and said, “a woman’s home should be the [whole] world” (The Calumet News).

Later that year, on September 20, 1912, one hundred Adams Township students gave a performance at the Kerredge Theater in support of women’s suffrage. At the time, the Kerredge Theater was an impressive theater house next to the Scott Hotel in downtown Hancock. It existed from the turn of the century through the end of the 1950s, when it burnt down. Having a show there was quite a feat; it could hold a remarkable 1500 theatergoers, and Sarah Berhardt, famous as an actress across the nation, performed there at one point. Cora choreographed the entire suffragist program, “The Dawn of a New Era,” herself and it raised ample funds for the movement. According to The Calumet News, she told a women’s meeting that the only reason the play wasn’t put on again at the Calumet Theater was the logistics and cost of getting the students up there.

Fred Jeffers also lent his authority and charisma to the cause. A 1914 article in The Calumet News reports that Fred gave a stirring speech at the Northern Michigan Normal School (later Northern Michigan University) in support of the suffragist movement. He was opposed to the British suffragettes using more militant tactics and told the crowd that their core message is not affected by their comrades’ violent strategies, echoing his speech about the pen being “mightier than the sword” that he had given at the oration contest decades earlier.

In 1918, when the men of Houghton County voted in favor of women’s rights to vote, Cora wired the election office in Detroit herself. “Victory for Houghton County!,” she wrote. In 1920, Cora was the first woman in her precinct to register to vote and she “never missed an opportunity to cast her ballot” (Rugani).

Fred and Cora never had children of their own, but Fred did reconnect with his family later in life. In 1905, when Fred was 36, he travelled with a colleague to Connecticut to meet his sister, who had been only a baby when the siblings were separated. The Menasha Record of Menasha, Wisconsin, reported on the reunion, explaining that “during the separation, neither had knowledge of the other’s existence.” She had been discovered after Fred had a memory of a sister and inquired into her whereabouts in newspapers, assumedly in Ohio where they were born. Hattie Brown of Groton was, ironically, also a teacher.

There are truly too many interesting accomplishments by Cora Jeffers to list them all. In 1934, when a state-of-the-art swimming pool was added to the school, Cora was determined to add to her P.E. repertoire and learned to swim at 63 years old. For the next 15 years of her career, and well into her 70s, she taught swimming classes. During the Great Depression, Cora and home economics students organized recipes inspired by rationing. During WWII she created a Victory Garden at home and encouraged others to do the same. When the young men of the area were going to be heading off to war, Cora learned pre-flight aeronautics so that she could teach it to the students who were to become pilots.

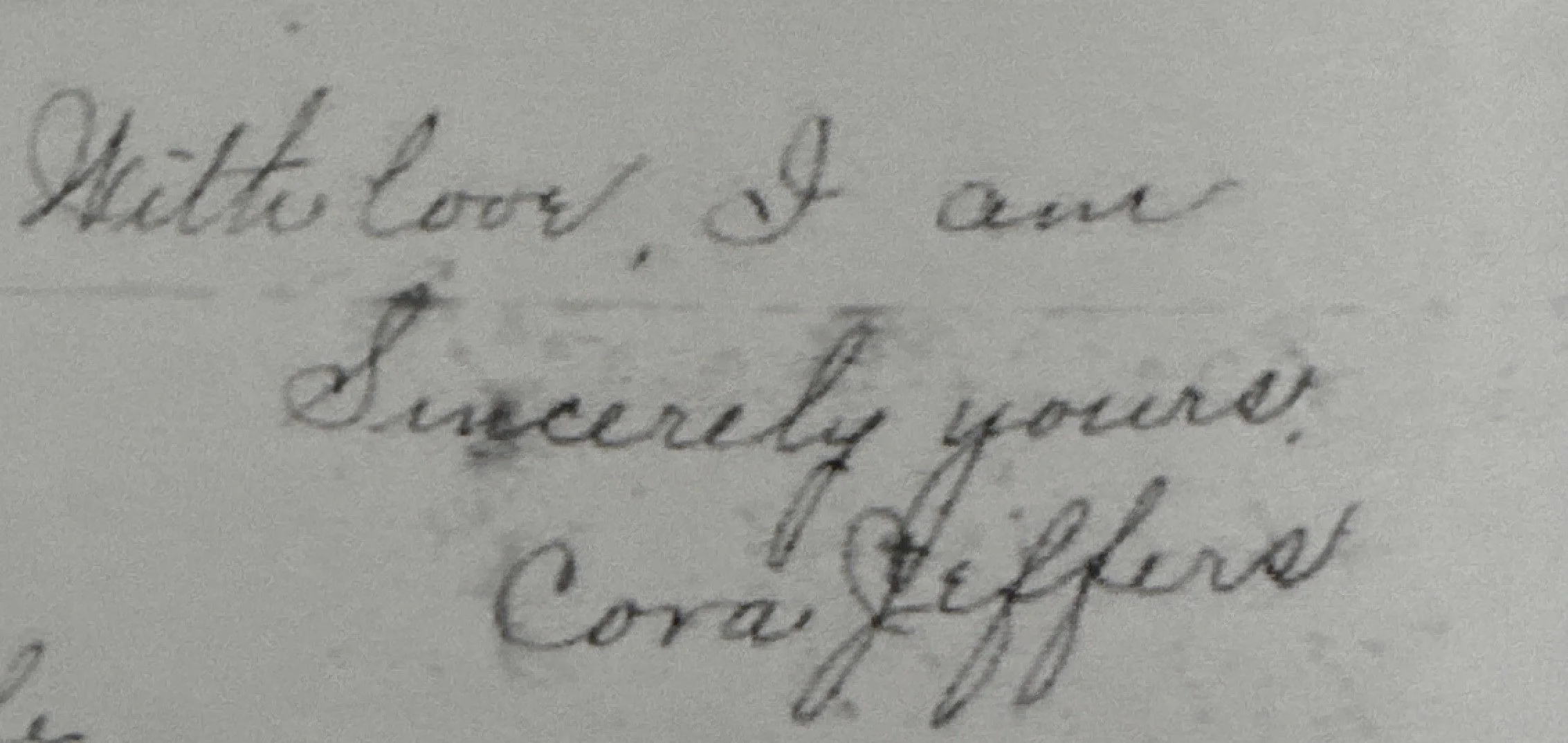

There is an example of a letter to a friend available in Dr. Frank Rugani’s book that really shows Cora’s tremendous character. Knowing her friend, Josephine, had recently been in the hospital (HIPAA did not exist yet, and newspapers would just publish who was in and out of the hospital), Cora wrote a kind letter of encouragement, explaining that her friend could get through these troubling times through hope. She ended the letter on a humorous note about raising her glass of “crystal water” to her friend’s health, as she did not drink alcohol.

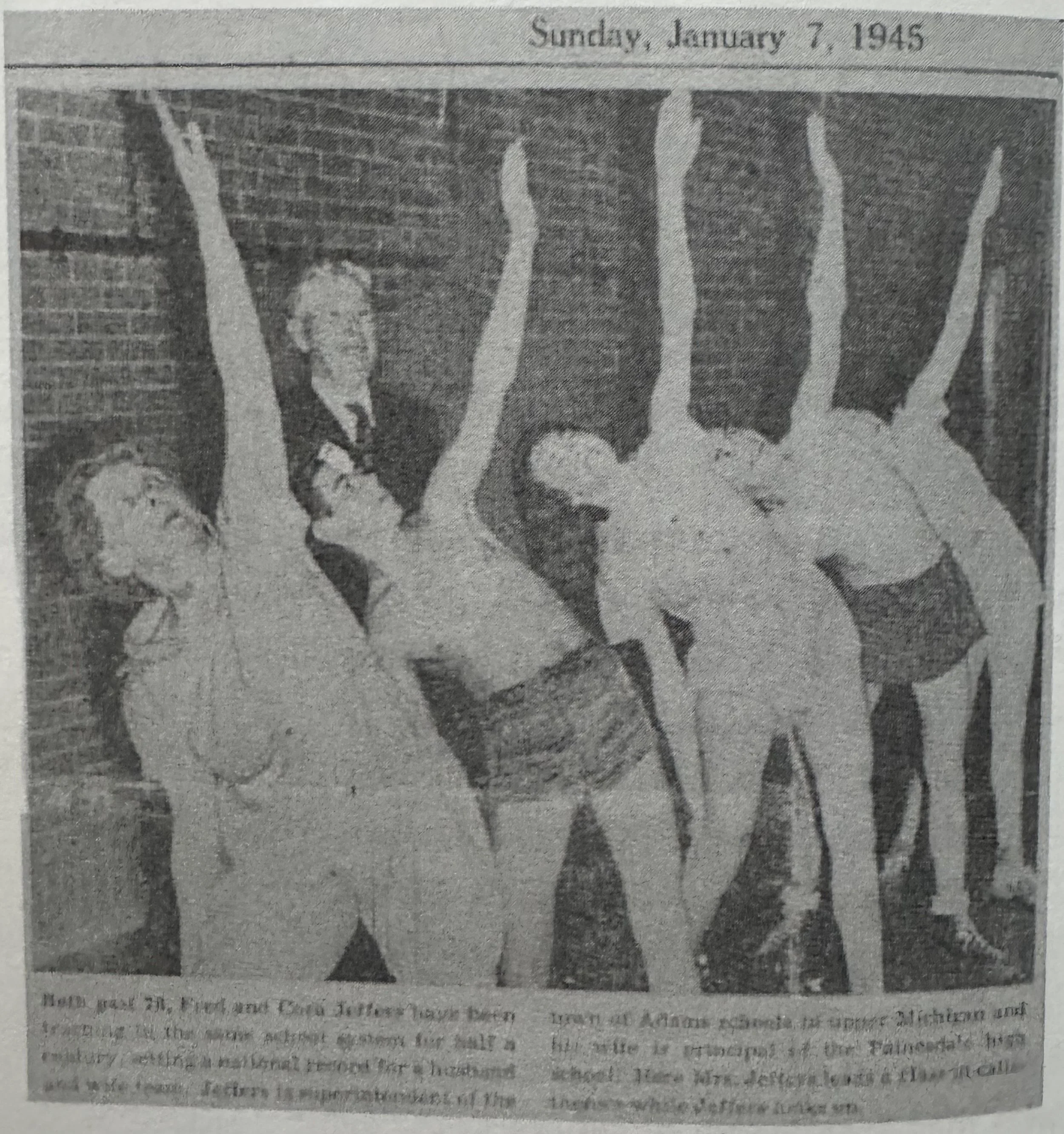

Cora and Fred served together as Principal and Superintendent, respectively, for 55 years in the Adams Township school district, from 1894 until 1949. A 1944 article from The Escanaba Daily Press proclaims that the pair held a national record for the longest time held by a “husband and wife combination in education, and they are still going strong.” Cora is described there as an “enthusiastic and energetic person,” which makes sense because it is later explained that everyday Cora teaches both a boys’ and girls’ P.E. class while “actually doing the acrobatic and folk dances, calisthenics, and gymnastics with the vim and vigor of youth,” quite an act for a woman in her 70s. The reporter from Escanaba spent the day with Cora and learned that she directs the school chorus at assembly every morning; eats only an orange for lunch every day; teaches two classes of Algebra, and an English class in addition to P.E., swimming and “fancy diving” everyday; and was also taking on many of the duties of her husband’s secretary while the woman participated in wartime efforts.

In 1945 TIME Magazine featured an article about the pair titled “Education: Partners” and, while a short read, it has so many interesting bits of information about their lives that it’s included here in its entirety:

“In a bustling copper-mining town high up on Michigan’s northern “thumb,” the year 1891 was a bad one for school-teaching. Three principals in a row were harried out of town by the unruly students. The clerk of Adams township asked for somebody who could use his two hands as well as the three Rs. He got a stocky, l80-lb. college boxer named Frederick Albert Jeffers.

At the first sign of rebellion when school opened the following September, Fred Jeffers seized the ringleader by the neck, bounced him up & down, and left him sprawling on the floor. After that school was quiet.

Last week Fred Jeffers, now grey, bespectacled and 76, was still keeping order in Adams township—as superintendent of schools. The principal of the high school in copper-mining Painesdale (pop. 1,270) is his wife, Cora Doolittle, 74. They have been married and fellow teachers for 51 years.

No Time for Theory. Cora and Fred Jeffers live in a tidy frame house across the street from the Painesdale high school. Cora is at her desk every morning at 7. (She has never missed a day.) She spends an hour cleaning up the mail. From 8 to 8:30 she advises students who have special problems. At 8:30 she conducts a singing class. At 9 she puts 60 to 90 boys & girls through a gym routine that often includes intricate steps from her rich repertory of folk dances. Then she teaches geometry, algebra, English, physics, chemistry and a variety of foreign languages until 3:30, when it is time to go home to clean house and start Fred’s supper. Fred spends his days on administrative chores, touring the schools, filling in as a teacher whenever necessary, and working on his sideline job as president of the township bank.

How to Keep Up. The Jeffers like their students to march to classes, be neat, honest, polite, and able to take orders. “I don’t want it understood that I’ve rejected the progressive philosophy,” says Fred. “Much of it is sound, but I think there has been weakness in its application.” When the school got a new swimming pool in 1934 Cora was 63 but she promptly learned how to swim, and took over the girls’ swimming classes. Last week she was teaching some beginners the side stroke. Two years ago, Cora added a course in aeronautics, taught it herself.

The teachers under them are expected to keep up, too; Fred often gives them tests on current events. Last week, in evenings at home Cora read H. V. Kalten-born’s / Broadcast the Crisis between snatches of Plato’s Republic. Fred shoveled a foot of snow off the sidewalk and read a book about Russia.

At the annual teachers’ ball, Cora dances mostly with her husband, who is one of the sweetest waltzers in the copper country, and also tries jitterbiigging. They are patently in love with each other—and with their profession. Said Fred Jeffers last week: “It’s a fine life.”

Adams Township admin and teachers in 1924. Fred is center, Cora to his left.

In 1949, the Adams Township Board of Education approved hiring J. H. Dunstan as Assistant Principal and granting Cora a three-month leave-of-absence. The expectation was that Cora would return after her rest with minimal duties besides training Dunstan to fully acquire the principal position. At the same time, the Northern Michigan College of Education was granted the right to confer honorary doctorate titles to two educators in Michigan. They had chosen both Cora and Fred to receive a “Doctor of Laws” degree. Unfortunately, only Fred would receive the honor, as Cora passed away during her leave, two days before her 78th birthday. Lorne Weddle wrote in her 1955 dissertation in Michigan History Magazine that Cora had “finally overworked her fine physique and died a martyr to her educational zeal.” Her doctors told Lorne after her death that she had “completely worn out her physical machine by the grilling program she carried out.” That summer, the Adams Township Alumni Association created an effort to rename the school to Jeffers High School. The Board of Education approved the change, and a formal banquet was given in Fred and Cora’s honor. Fred, of course, gave a compelling acceptance speech. He retired the following spring and moved to Florida.

Cora’s influence has never faded from Adams Township. Students still file into the school building that she and Fred worked so hard to bring to life in Painesdale, and her swimming pool continues to serve new generations in physical education classes. Her name is spoken every single day through Jeffers High School, a lasting reminder of her belief in possibility, hard work, and community. Her story lives on in the halls of the building she helped build and in the young people who continue to learn in its classrooms.

Sources:

Adams Township School District. “District History.” Adams Township Schools. Accessed 2025. https://adamstownshipschools.org/district-history.php.

Michigan Technological University. “Flashback Friday: Hallowed Halls on Hollowed Ground.” Michigan Tech Archives blog. June 28, 2019. https://blogs.mtu.edu/archives/2019/06/28/flashback-friday-hallowed-halls-on-hollowed-ground/.

The Calumet News. Various articles on Cora Doolittle Jeffers and suffrage, 1912–1914. Newspapers.com digitized newspaper collections.

CopperRange.org. “School Train.” https://www.copperrange.org/school.htm.

Escanaba Daily Press. “Educator Pair Holds National Record.” Article on Cora and Fred Jeffers. 1944. Digitized newspaper archives.

EMU Digital Commons, Eastern Michigan University. Photographic collections relating to Michigan State Normal School (Ypsilanti), including campus, classrooms, and commencement scenes, various years. https://commons.emich.edu/commencement/index.26.html.

Life Magazine Archives. Search conducted; no article on Cora or Fred Jeffers found.

Michigan State Normal School. Normal News Oration Contest coverage and commencement reports. Various issues, 1890–1891. Digitized by EMU Archives.

Weddle, Lorne. “Cora Doolittle Jeffers, Outstanding Educator, Was U.P. Teacher.” The Mining Journal. December 1, 1955.

Rugani, Frank. Adams Township Schools: A History. Self-published monograph. 2009.

Stanton Township Historical Documents. “School Train Articles” and “School Train by Brinkman” PDFs. https://www.stantontownship.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/.

Time Magazine. “Education: Partners.” TIME, December 3, 1945. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0%2C33009%2C852523%2C00.html.

The Menasha Record. Article on Fred Jeffers’s reunion with his sister, 1905. Newspapers.com digitized newspaper archives.

The Ypsilanti Commercial. Coverage of Michigan State Normal School commencement, 1891. Digitized local newspaper collections.